Location: The AnteRoom, Kattenberg 93, 2140 Borgerhout

This show ran simultaneous with (and as part of the programme of) the Contemporary Art festival BHART#1 in Borgerhout – Antwerp from 07 to 16 September 2012.

See pictures of the show > here <

the journal of the Institute of Idle Curiosity for Elements of Seduction

Location: The AnteRoom, Kattenberg 93, 2140 Borgerhout

This show ran simultaneous with (and as part of the programme of) the Contemporary Art festival BHART#1 in Borgerhout – Antwerp from 07 to 16 September 2012.

See pictures of the show > here <

[text and image credits: Gaston Meskens for The Arts Institute]

[text written on the occasion of the show ‘Images and colors’ of Stijn Cole with Galerie Van de Weghe]

Onze natuur, of de politiek van de gelatenheid.

Vandaag is Darwin multi-inzetbaar. Hij wordt er bij gehaald om verdachte religieuze standpunten onderuit te halen, maar ook om ons eraan te herinneren dat we als mens niet al te stoer moeten doen in onze relatie met de natuur. We staan niet boven de natuur maar maken er deel van uit, en als we die relatie verstoren worden we daar simpelweg zelf slachtoffer van.

Met alle aandacht die Darwin krijgt zouden we Herbert Spencer nog vergeten. De bekende uitdrukking ‘survival of the fittest’ komt namelijk van hem, en het was Darwin die ze overnam in de vijfde editie van zijn Origin of Species. Maar Spencer was een filosoof die Darwin las met een bedenkelijke bedoeling: hij wou het idee van ‘natuurlijke selectie’ toepassen op zijn economische, sociale en zelfs ethische theorieën. Spencer’s ambitie was de ontwikkeling van een allesomvattende evolutieleer die niet alleen de fysieke natuurlijke wereld beschrijft, maar ook het wat, hoe en waarom van mens en maatschappij. Die ruime blik is op zich niet controversieel, maar Spencer was een soort hybride positivist. Hij geloofde dat niet alleen de natuur, maar ook alles wat ons mens maakt werkt volgens de logische wetten van de mechanica en de wiskunde. En hij was hybride omdat hij op het toppunt van zijn carrière ook het ‘rationele geloof’ in een transcendente niet-ingrijpende god proclameerde. Die combinatie van deïsme en positivisme maakte hem populair in een moderne tijd waarin wetenschap beloofde ons algemeen praktisch welzijn te gaan verzekeren, maar er blijkbaar toch niet direct in slaagde om ons onbehagen rond de vragen des levens weg te nemen.

Het denken over totaalsystemen die niet alleen de samenhang van mens en natuur verklaren maar ook ons bestaan betekenis en zin moeten geven is even oud als de intelligente reflecterende mens zelf. In de moderniteit van de vorige eeuw werden ze systematischer uitgewerkt, maar niet noodzakelijk altijd rationeel wetenschappelijk. Want ook de moderniteit kende haar tegenbewegingen, hetzij via spiritualiteit, hetzij via kunst, en dikwijls via een combinatie van de twee.

Hou Spencer even in gedachten, want dit verhaal neemt nu een andere invalshoek. Het schoolvoorbeeld van de ideologie van het geheel van mens en natuur, gedragen door kunst en spiritualiteit, is waarschijnlijk wel het Bauhaus. Johannes Itten maakte deel uit van de originele kerngroep van de Bauhaus school en was ook een systeem- en totaaldenker. Als aanhanger van de Mazdaznan leer kon hij echter niet van koud mechanistisch positivisme beschuldigd worden. Mazdazdan was een religie die voorhield dat de aarde zou moeten hersteld worden als één grote tuin waarin de mensheid zou kunnen samenwerken en converseren met god. De religie bouwt voort op de oude religieuze filosofie van Zarathustra, een visie die stelt dat alles in feite een strijd is tussen twee tegengestelde oerkrachten: de verhelderende wijsheid en de destructieve geest; een filosofie die zoals gekend ook Nietzsche inspireerde. Die strijd had voor Itten echter niets te maken met een survival of the fittest. Itten geloofde in het unieke en in de kracht van elke mens en ook dat die via individuele meditatie en creatieve samenwerking tot uiting konden komen. In zijn kleurenleer stelde hij ook dat elke mens, voorbij sentimentele en persoonlijke voorkeuren, objectief in staat is om sets van kleuren te associeren met de vier seizoenen. Dit was voor hem een bewijs voor onze diepe verbondenheid en harmonie met de natuur. Maar Bauhaus voorzitter Walter Gropius was eerder geïnteresseerd in massaproductie ten dienste van de esthetische emancipatie van het volk. Hij zag geen heil in mystiek of in het stimuleren van individuele artistieke expressie. Itten werd bijgevolg met kleurenleer en al weggestuurd van de school.

Spencer nam uiteindelijk afstand van het idee van de transcendente god en concentreerde zich op zijn positivistisch wereldbeeld, en Itten concentreerde zich dan maar op onderwijs in kunst en ambacht en uiteindelijk op zijn eigen schilderkunst. In functie van het modernisme was de beoogde harmonie van Spencer pragmatisch maar pervers, en die van Itten spiritueel maar blijkbaar inefficient.

En Darwin? Die wordt vandaag vooral misbruikt. Darwin leerde ons iets over hoe we evolueren, maar zei wijselijk niets over waar we vandaan komen. En toch gebruiken wetenschappers en spiritisten hem nog steeds om aan te tonen dat de ander ongelijk heeft. Vandaag bestaan tegengestelde visies op totaalsystemen comfortabel naast elkaar, en de ideologie van het pluralisme en de tolerantie bouwt niet zozeer op respect voor de visie van de ander, maar dient vooral om die van zichzelf te beschermen. Dat geldt ook voor onze relatie met de natuur. Wetenschappelijke en spirituele goeroes lopen elkaar niet voor de voeten, maar geen van beide kan de natuur en de mens redden. Ze kunnen het niet omdat ze de melancholie van onze relatie met onze natuur niet kunnen uitdrukken. De natuur sparen is onszelf sparen, maar die motivatie vereist gevoel voor esthetiek, en kan dus nooit zuiver rationeel zijn. En die esthetiek is melancholisch, want wat we als mens ook doen, steeds opnieuw zal de natuur het van ons overnemen. Eensgezinde gelatenheid is dus deel van onze verantwoordelijkheid, en als houding nog veel moeilijker te vertalen in politieke maatregelen dan zelfbescherming.

Onze natuur, of de kunst van de terughoudendheid.

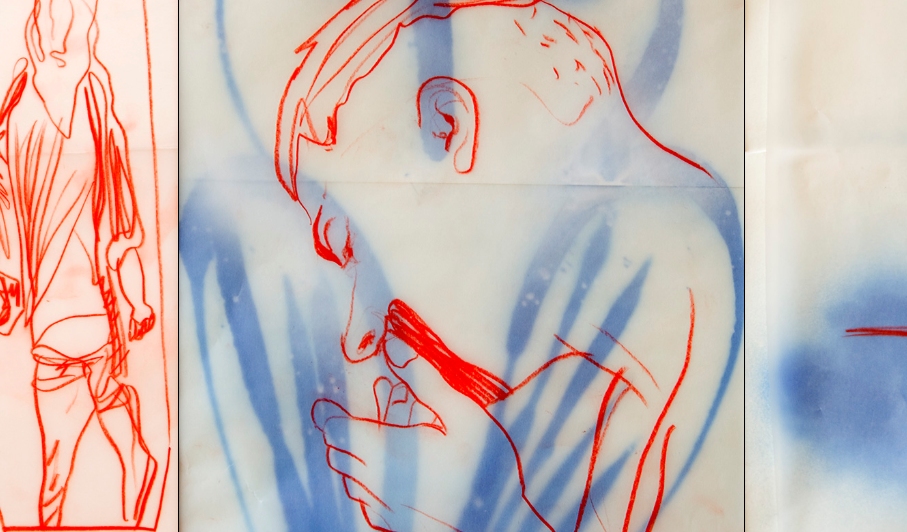

In ‘Images & Colors’ toont Stijn Cole samenstellingen van tekeningen, foto’s en kleurenschema’s. Als iemand ooit op het idee zou komen om zijn werk op te stellen in een didactisch-wetenschappelijke tentoonstelling over natuurbehoud, dan zouden de bezoekers op het eerste zicht kunnen denken dat hij een wetenschapper is die gesofistikeerde analyses van vegetatie en landschap verricht. Als ze hun tijd zouden nemen om beter te kijken zouden ze echter voelen dat er iets niet klopt. Zijn ‘displays’ bevatten geen duidelijke vaststellingen, conclusies of aanbevelingen. Maar net daarom zouden ze in die vreemde setting op hun plaats zijn. Hun analytische terughoudendheid zou namelijk als voorbeeld kunnen dienen voor al die te zelfzekere ‘echte’ wetenschappelijke ratios over onze relatie met de natuur. Het werk van Stijn Cole zou ook stiekem in een tentoonstelling over het Bauhaus kunnen binnengesmokkeld worden. Zijn ‘kleurenleer’ verwijst echter niet naar een totaalharmonie, maar naar het door tijd en complexiteit onvermijdelijk gefragmenteerde van de waarneming van de habitat rondom ons. Of hij het nu wil of niet, Stijn Cole toont wat wetenschap en spiritualiteit niet kunnen: voorbij de ratio van natuurexploitatie en natuurbehoud zal de relatie van de mens met zijn habitat altijd melancholisch zijn. Wetenschap, politiek en ethiek van natuurbehoud zijn waardeloos zonder de esthetisch-melancholische blik.

Gaston Meskens

VN Klimaatconferentie, Warschau, 18 November 2013.

[Link to Stijn Cole, Galerie Van De Weghe]

The AnteRoom is the lobby of The Arts Institute, located at Kattenberg 93 in Borgerhout – Antwerp. The Arts Institute is the public department of the Institute of Idle Curiosity for Elements of Seduction. As the research labs of the institute are not open to the public, the AnteRoom functions also as their front reception and show space. Abandoned research artefacts from the labs are continuously on view, and currently also preparations for a next project in cooperation with Extra City, Antwerp.

De AnteRoom is de lobby van The Arts Institute, Kattenberg 93, Borgerhout – Antwerpen. The Arts Institute is het publieke departement van het Institute of Idle Curiosity for Elements of Seduction. Omdat de onderzoekslabo’s van het instituut niet toegankelijk zijn voor het publiek fungeert The AnteRoom ook als hun ontvangst- en tentoonstellingsruimte. Er worden permanent afgedankte onderzoeksobjecten getoond, en momenteel ook de voorbereidingen voor een volgend project in samenwerking met Extra City.

Location: The AnteRoom, Kattenberg 93, 2140 Borgerhout

Official opening of The AnteRoom: Friday 7 September 2012, 21h00 – 24h00

This show runs simultaneous with (and as part of the programme of) the Contemporary Art festival BHART#1 in Borgerhout – Antwerp (see www.bhart.be)

Opening hours:

– Saturday 8 September 2012: 13h00 – 19h00

– Sunday 9 September 2012: 13h00 – 19h00

– Friday 14 September 2012: 13h00 – 17h00

– Saturday 15 September 2012: 13h00 – 17h00

Visit by appointment: +32 473 97 50 72

“Kunst kan slaan en zalven, maar eigenlijk willen we er allemaal stiekem door getroost worden. De gedachte dat kunst geen politieke of wetenschappelijke waarheid kan uitdrukken is daarbij dan al een goed begin.”

De kneedbare kunstenaar (Zoals verschenen in <H>ART Magazine #97)

In juni komt de wereld samen in Rio de Janeiro voor een nieuwe politieke top rond duurzame ontwikkeling. Tijdens dat grootste politieke evenement van de laatste tien jaar komen politici, wetenschappers en activisten hun mening geven over hoe het met onze wereld gesteld is. Er worden geen kunstenaars uitgenodigd. Dat is misschien vreemd, want vandaag is hun mening over de staat van de planeet en de maatschappij belangrijker dan ooit. De politiek geëngageerde kunstenaars gaan echter niet naar Rio, maar naar Berlijn. De Biënnale daar hoopt expliciet dat de acties van de uitgenodigde kunstenaars ter plaatse niet alleen kunst opleveren, maar ook een ‘politieke waarheid’ zouden onthullen en mee ‘verandering’ inzetten[1]. Geen beelden maar daden?

Die vraag naar politieke waarheid in kunst vervoegt vandaag die andere heikele vraag rond wetenschappelijke waarheid in het kunstdebat. De discussie rond het doctoraat in de kunsten gaat nog steeds over de vraag of de kunstenaar als onderzoeker ‘objectief’ de methode, waarde en ‘resultaten’ van zijn onderzoek kan aantonen via het werk alleen of, indien niet, het werk ook gepaard moet gaan met duiding als deel van het doctoraat. Geen beelden maar woorden?

Ik vind het prima dat de kunstenaar uitgenodigd wordt om politieke en wetenschappelijke waarheden aan te brengen. Hij kan dan namelijk tonen dat zoiets onmogelijk is. En als hij wil kan hij tegelijk de politicus en de wetenschapper op hun eigen beperkingen in die zin wijzen: via kunst, met inbegrip van woorden en daden… Over dit soort kunst gaat dit stuk. De kunstenaar is niet meetbaar maar wel kneedbaar, en dat heeft hij zelf in de hand.

Het comfort van de polarisatie

Globalisering, milieuvervuiling, klimaatverandering, economische crisis, terrorismedreiging en religieuze conflicten zetten vandaag de politieke agenda, en in die kwesties staat de geloofwaardigheid van de politicus en de wetenschapper met betrekking tot hun maatschappelijke rol en verantwoordelijkheid onder druk. De wetenschapper haalt zijn geloofwaardigheid uit de claim dat hij autonoom kan handelen omdat hij objectief is. De politicus daarentegen haalt zijn geloofwaardigheid uit de claim dat hij autonoom mag handelen omdat hij verkozen is. Maar het publieke en politieke discours waarin de wetenschapper en de politicus positie innemen rond die kwesties is vandaag vooral populistisch en daardoor polariserend. In het licht (of in de duisternis) van de onzekerheid en complexiteit die deze kwesties kenmerken raakt het wetenschappelijke discours meestal niet voorbij discussies rond conflicting truths, terwijl het politieke steeds weer terugvalt op stellingnames tussen conflicting identities. Zowel in wetenschappelijke als in politieke argumentaties leiden strategische vereenvoudigingen van onzekerheid en complexiteit tot polarisaties waarin het handhaven van de eigen comfortzone belangrijker lijkt dan een toenadering met het oog op consensus.

De kunst vooruit

Deze tekst heeft niet de bedoeling de maatschappelijke rol en verantwoordelijkheid van de wetenschapper en de politicus te vergelijken met die van de kunstenaar, om de simpele reden dat geloofwaardigheid geen sleutelwoord is voor de hedendaagse kunstenaar. De kunstenaar is niet verkozen, hoeft niet objectief te zijn en heeft ook niets te bewijzen. Waarom dan toch een reflectie vanuit de kunst in de richting van wetenschap en politiek? Een gemeenschappelijk kenmerk van hun maatschappelijk functioneren is dat ze alle drie een appel doen op de buitenwereld in de manier waarop ze dwingende uitspraken doen over de sociale realiteit; dwingend omdat ze van hun publiek verwachten dat het met die uitspraken rekening houdt. Daarvan hangt voor elk van hen hun bestaansreden en ook hun erkenning af. De kunst is echter als enige van de drie doorheen de moderne geschiedenis haar eigen geloofwaardigheid beginnen onderzoeken. Het historische verhaal van de kunst vanaf het modernisme tot vandaag kan namelijk gezien worden als een gradueel proces van kritische zelfreflectie. De kunst heeft zelf haar eigen methode in vraag gesteld en daarmee ook tot het uiterste haar eigen identiteit ondermijnd. Noch de verlicht-moderne wetenschap noch de verlicht-moderne politiek heeft tot vandaag een gelijkaardig zelfkritisch proces georganiseerd.

Reflexiviteit als activisme

Men kan aanbrengen dat er voor kunst veel minder op het spel staat dan voor politiek en wetenschap, en dat haar oefening in reflexiviteit daarom hoe dan ook ‘veilig’ was en nog steeds is. Dat is echter het punt niet. Wetenschap en politiek worden inderdaad uit zelfbescherming en in de hang naar publieke erkenning (voor de wetenschap ook vanuit de markt) in strategische stellingnames gedwongen. Maar tegelijk neemt vanuit maatschappijkritische hoek ook de druk toe op wetenschap en politiek om in de complexe wereld van vandaag hun strategische posities rond waarheid en identiteit te verlaten. Die kritiek vertrekt vanuit het idee dat complexe sociale fenomenen essentieel ‘ondefinieerbaar’ zijn en dat behalve in de wiskunde definities alleen maar reducerende metaforen zijn die op hun beurt vatbaar zijn voor misbruik. Als de nood hoog is moeten ook metaforen gedelibereerd worden.

De grijze en mistige implicatiezone waarin de wetenschapper en de politicus vandaag zou moeten binnentreden is die plaats waar ze als wetenschapper en politicus ook kunnen spreken over wat ze geloven maar niet kunnen bewijzen, vrezen maar niet kunnen hardmaken en hopen maar niet kunnen garanderen. Het is een plaats waar gezamenlijk ‘kritisch maar mededogend’ wetenschappelijke disciplines doorkruist worden en politieke stellingen ontmanteld. Die plaats is dwingend want ze impliceert transparantie, reflexiviteit en deliberatie. Maar net daardoor kan ze ook bevrijdend werken. En omdat men er geëngageerd kan doorkruisen en ontmantelen is die plaats dezelfde als diegene waarin de kunstenaar ‘vanuit de andere richting’ terecht komt als hij zich afvraagt hoe en wat zijn onderzoek en activisme kan bijdragen en of het dan nog wel kunst dan wel wetenschap of politiek is. Een reflectie over de manier waarop de hedendaagse kunstenaar zich vandaag in de maatschappij kan profileren als onderzoeker of politiek activist is daarom niet alleen interessant voor de kunstwereld zelf, maar ook voor die wetenschapper en politicus die zich geconfronteerd ziet met de onmogelijkheid om de bovengenoemde kwesties te reduceren tot een simpele ratio die meteen ook de eigen positie met betrekking tot waarheid en identiteit zou dienen. De ‘kritische spiegel’ die kunst zo de politiek en de wetenschap kan voorhouden is er één die wijst op het ambivalente van hun positie en het problematische van het strategisch misbruik daarvan. Het ophouden van deze spiegel is geen verantwoordelijkheid voor hedendaagse kunst, maar eerder een interessante en logische volgende stap in haar eigen reflexief onderzoek met betrekking tot haar rol als maatschappelijke actor. Met andere woorden: kunst ‘moet niets’, maar als ze zich nog wil bezighouden met activisme of onderzoek dan is de bovengeschetste stap noodzakelijk en onvermijdelijk. Reflexiviteit als activisme dus. De zelf georganiseerde implicatiezone fungeert daarbij ook als antichambre naar doordachte actie in de maatschappij. Deze actie vanuit de kunst zal echter steeds ook gelaten zijn, net omdat ze vertrekt vanuit het inzicht dat ze, in antwoord op het rationeel waarheids- en identiteitsdenken, als kunst enkel twijfel kan zaaien door zelf openlijk te twijfelen.

De nieuwe zakelijkheid

Maar vandaag zien we in de kunst dikwijls het omgekeerde gebeuren: in plaats van gezonde twijfel te zaaien over de beloftes en potenties van politiek en wetenschap eigenen meer en meer kunstenaars, op zoek naar erkenning in de overmaat en waan van de dag, zich het aura van activist of onderzoeker toe, en als ze gevraagd worden naar de sociale relevantie en beoogde politieke implicaties van hun werk schermen ze zich dikwijls af met de stelling dat ze kunstenaar zijn, en geen politicus of wetenschapper. Op zoek naar snelle erkenning in het gemediatiseerde politieke discours riskeert de kunstenaar daarbij terug te vallen op dezelfde stereotypen als die gebruikt door diegene die hij viseert. Het cynisch uitvergroten van deze stereotypen is daarbij van alle mogelijke ‘kritische houdingen’ alleszins de gemakkelijkste en, als ze dan nog in de vorm van spektakelkunst gepresenteerd wordt, ook nog eens de meest geschikte om publieke aandacht te trekken. Niet alleen vanuit de kunstkritiek en de academie maar zelfs vanuit de markt wordt er meer en meer een terughoudende en kritische houding aangenomen ten opzichte van cynische spektakelkunst of zelfgenoegzame shock art met een veelal oppervlakkige maatschappijkritische boodschap op basis van een dun idee. Men merkt dat steeds meer jonge kunstenaars in de ‘mature art world’ (zeg Europa & de VS) terugplooien op het maken van poëtisch werk en geen politieke standpunten meer willen innemen (uit angst om naïef gevonden te worden?) terwijl dat in de ‘emerging art world’ (vb China), als deel van hun politiek emancipatieproces, wel nog het geval is.

Kunst als onderzoek – onderzoek als kunst

Terwijl de (jonge) kunstenaar vandaag bij ons eerder aarzelt om zich te profileren als politiek activist blijft hij wel de attitude en het jargon van de wetenschapper overnemen. Hij profileert zich als onderzoeker en wil dat de maatschappij dat onderzoek ernstig neemt. Dat heeft onvermijdelijk gevolgen voor een formalisatie van de onderzoekspraktijk in de vorm van het doctoraat in de kunsten. Bij de beoordeling van dat doctoraat moeten de kunstenaar-onderzoeker en de beoordeler bereid zijn de onderzoeksmethode zo te bepalen dat ze mogelijkheid tot doordachte evaluatie toelaat. Dat betekent onvermijdelijk dat het niet volstaat om ‘het werk voor zich te laten spreken’, en dat de kunstenaar zich zal moeten engageren in het geven van duiding. En die duiding kan zondermeer kunstzinnig zijn, en illustratief voor de klassieke wetenschapper. Onderzoek als kunst dus, want aangezien de kunstenaar zich typisch wil uitdrukken en raken ‘zonder te verklaren’ kan een doctoraat in de kunsten niets anders impliceren dan dat de kunstenaar gaat voor het behalen van de graad van ‘doctor in de zelfbeschouwing’…

Kunst als activisme – activisme als kunst

Kan kunst dan het activisme redden? In New York en elders werden de indignados strategisch aan de kant gezet. Ze konden zich niet verweren omdat ze enkel ontevreden waren, en er prat op gingen dat ze geen stelling te verdedigen hadden. Het komen tot een gezamenlijk standpunt zou toch alleen maar weer hiërarchie en ellebogenwerk veroorzaken, en dat was net het doel van hun protest. Een bijzonder initiatief heeft daardoor een kans gemist. Vandaag staan de betogers niet meer op Wall Street, maar in de exporuimtes van de Biënnale van Berlijn. En dat vinden de technocraten, beursspeculanten en andere Cynical Executive Officers prima. Misschien kopen ze daar nog wel iets voor hun collectie.

Entering de kunstenaar-activist. Een trend in de kunst die nog dikwijls over het hoofd gezien wordt is die van de kunstenaar die meer en meer als publieke figuur op de voorgrond treedt. Als hij niet gedwongen wordt over zijn werk te praten wil hij dat blijkbaar wel spontaan doen, mét analyse van de staat van de wereld erbij. Dat is op zich geen slechte zaak, want hij zou nu samen met de ontevredenen confronterende gedachten kunnen formuleren. In plaats van polarisaties te versterken zouden ze samen in Berlijn én in Rio implicatiezones kunnen creëren waarin ze eerst met zichzelf in debat gaan en in tweede instantie de geviseerden uitnodigen. Activisme als kunst erkent dat er vandaag geen comfortzones meer zijn voor sociaal engagement. Het is nog niet te laat.

Tot slot

Kunst kan slaan en zalven, maar eigenlijk willen we er allemaal stiekem door getroost worden. De gedachte dat kunst geen politieke of wetenschappelijke waarheid kan uitdrukken is daarbij dan al een goed begin.

Gaston Meskens, 31 mei 2012

[1] Artur Żmijewski, 7th Berlin Biennale For Contemporary Politics, http://www.berlinbiennale.de/blog/

< reflection space / confrontation place >

A reflection on art as activism today

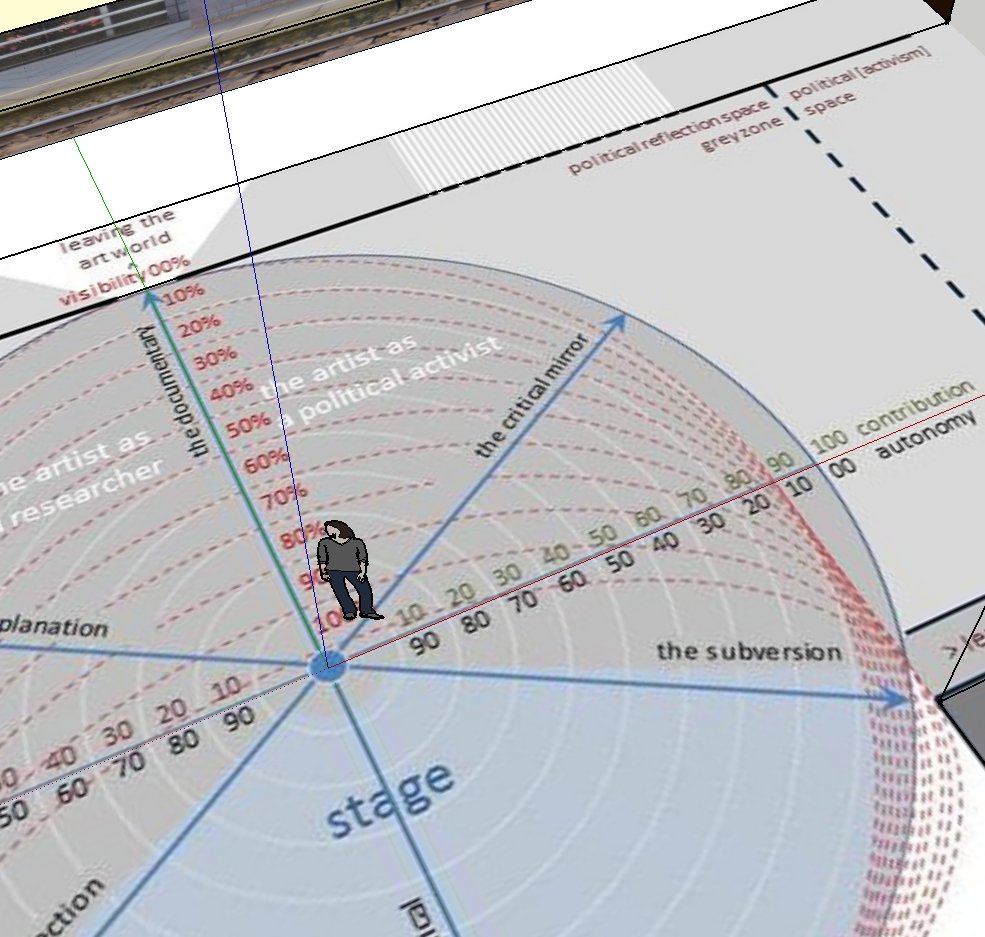

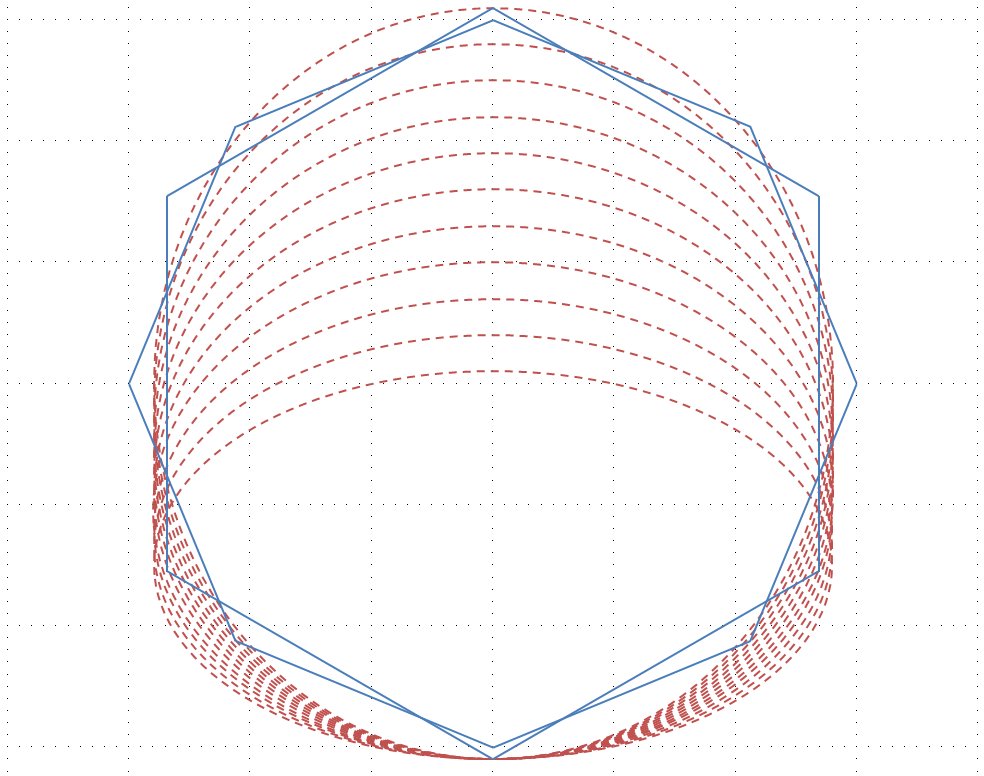

Has art as political activism reached its limits, sterilised as it seems to be in a mediatised society stressed by hyper-connection, total visibility and cynically appropriated freedoms of speech? And what can be retained from its original subversive potential for current on-going processes of democratisation and emancipation?

This lecture done at the Rijksakademia Amsterdam on 12 May 2012 inquires into what artistic agency in the form of political activism can still mean today. It does however not have the ambition to ‘compare’ the agency of politician with that of the artist, and this for the simple reason that ‘credibility’ is not a relevant concept for the artist’s functioning in society: the contemporary artist is not elected, does not need to be objective and has nothing to prove. However, a (self)reflection on contemporary artistic activism may not only be interesting for art as such but essentially also for the political that finds itself confronted with the impossibility to reduce arguments on complex socio-political issues to simple ratios that would primarily serve its own legitimacy constructed around its own truths and identities. In doing a “self-reflection on agency” in the form of an art practice, art could thus keep up a ‘critical mirror’ in front of politics; a mirror that shows the ambivalence of political positions and unveils the problematic character of eventual strategic misuse of this ambivalence

The lecture argues that this ‘avant-garde of deliberate self-relativisation’ is actually the only possible route for art as activism, and that its subversive and emancipating potential is in the way it can undermine the comfort of polarisation that marks contemporary politics rather than to choose side in that polarisation.

Check the visuals used in the lecture > here < .

tekst bij de show van

COLIN WAEGHE – ALTERNATOR – 23 Postcards From The Antipodes

In ALTERNATOR – 23 Postcards From The Antipodes toont Colin Waeghe olieverfschilderijen en tekeningen in inkt. We zien onder andere Jan Palach en Rosa Parks, maar ook Francis Bacon en William Burroughs in ‘gedrukte beelden’ die qua vorm lijken op de befaamde Künstlerplakate die de niet-‘officiële’ kunstenaars in Oost-Duitsland tussen 1967 en 1989 drukten. Door de oplage steevast kleiner dan 100 te houden konden ze maximaal hun boodschap verspreiden en toch ontsnappen aan de censuurcommissie. Colin Waeghe’s postcards zijn pamfletten gedrukt op één exemplaar. Ze werden gemaakt en verstuurd vanuit het oerwoud. The jungle zien als een broedplaats voor anti-establishment strategieën lijkt alvast niet echt logisch. In de jungle heersen immers geen normen of reglementen, en kan er dus ook geen onderdrukking en nood aan opstand zijn. Echter, er wordt gezegd dat in de jungle het recht van de sterkste heerst, en soms ook dat er chaos heerst. Maar het recht van de sterkste en chaos bestaan niet in de natuur, want recht en chaos zijn menselijke concepten. De natuurlijke jungle heeft haar eigen interne logica, keihard maar betekenisloos, niet strategisch maar ook niet vrijmoedig. Ze is daarom de antipode van de menselijke wereld waarin de logica van de traditie en het conformisme steeds die van de nieuwsgierigheid en de bevrijding probeert te onderdrukken. In onze beschaving blijft het oerwoud de metafoor voor de oernatuur, maar vandaag moet dat oerwoud beschermd worden in plaats van uitgerookt. Nee, de broedplaatsen voor verzet die opgevoerd worden in deze show zijn niet de natuurlijke, maar wel die plaatsen waar macht zich manifesteert, hetzij onderdrukkend politiek-autoritair, hetzij verstikkend sociaal-conformistisch.

En net in dergelijke omgevingen lijkt een kritisch mens op zoek naar zingeving gedoemd om zich ‘onlogisch’ te gedragen, in extreme gevallen met gevaar voor het eigen leven. Er zijn daarbij twee menselijke drijfveren die op het eerste zicht diametraal tegenover elkaar staan, en die twee devianten zijn in de show vertegenwoordigd: de politieke anti-establishment activist en de sociaal-anarchistische non-conformist. En Palach en Burroughs kunnen doorgaan als de twee uitersten daarvan. Met zijn politiek activisme voor vrijheid offerde Palach letterlijk zijn leven op. Burroughs, Bacon en hun hedendaagse kompanen (Kurt Cobain komt als eerste voor de geest) evoceerden daarentegen als kunstenaars een escapisme dat zich afzette tegen de conformistische maatschappelijke mediocrity met haar praktische beslommeringen. Ze waren sociaal maar de goede zaak kon hun (zogezegd) gestolen worden. In Heaven and Hell gebruikt Aldous Huxley trouwens de term antipode als deze ‘regions of the mind’ die alleen kunnen bereikt worden met meditatie, zelfkastijding, vasten en vooral ‘specific chemical substances’. Met hun levensstijl en roesexperimenten brachten ze op hun manier ook hun leven in gevaar. Als uiterste vertegenwoordiger van deze ‘afwijking’ vernietigde Burroughs ook het leven van zijn geliefde. Hij schoot tijdens een absurde dronken evocatie van Willem Tell per ongeluk zijn vrouw dood, en deze gebeurtenis zal de rest van zijn leven en zijn kunst tekenen.

De paradox is dat, als men deze devianten van beide zijden zou vragen waarom ze deze levensstijl aanhouden, ze zouden antwoorden dat dit het enige logische is wat ze kunnen doen (met uitzondering misschien van het per ongeluk doden van hun naasten). Ze weten niet waaraan ze beginnen, maar wel waar het gaat eindigen. Hoe logisch voor hen ook, zowel het activisme van Palach en Parks als het sociaal anarchisme van Burroughs en Bacon zijn voor de meeste mensen ondenkbaar, niet omdat deze levens praktisch onbereikbaar zouden zijn, maar wel omdat men er zich ergens wel toe aangetrokken voelt, maar men er tegelijk heel bang van is. Het gros van de mensheid is toeschouwer van dergelijke taferelen. Palach en Parks stellen de ethiek van die toeschouwer op de proef, en Burroughs en Bacon houden hem een esthetische spiegel voor. De toeschouwer krijgt postcards te zien, verstuurd vanuit een plaats waar zich een bepaald tragisch maar fascinerend gebeuren afspeelde. De werken van Colin Waeghe suggereren dat het publiek de gesuggereerde scènes zou moeten kennen, maar ook dat het daarbij altijd buitengesloten zal zijn, niet omdat het niet mag meedoen, maar omdat het niet durft. Er wordt de gemiddelde kijker duidelijk gemaakt dat hij/zij er, omwille van ethische luiheid of ethisch defaitisme, of door esthetische middelmatigheid of zin voor kitsch, waarschijnlijk nooit bij zal horen. Ik zeg waarschijnlijk, want Colin Waeghe geeft hen nog een kans. Tussen de namen van de activisten en escapisten voegt hij namen van zijn vrienden en kennissen toe, alsof hij wil suggereren dat het iedere welvarende mens gegeven is om politiek activist of sociaal-esthetisch escapist te worden. Maar in onze gemediatiseerde maatschappij, waar de grens tussen realiteit en fictie voorgoed vervaagd lijkt, is het tweede, weliswaar vanop veilige afstand, aanlokkelijker. Want waarom dwepen we wel met Burroughs en niet met Palach? Waarom hebben we respect voor Palach maar vinden we stiekem Burroughs de coolste van de twee? Deze houding zou wel eens het ultieme conformisme kunnen zijn: als loser hém vereren die van het loser zijn een stuntelige maar intelligente performance maakt. Dat is veel interessanter én eenvoudiger dan iets te doen met dat lastige knagende geweten dat opduikt bij het aanhoren of aanschouwen van de verhalen van Palach en Parks.

De postcards zijn meer dan lastige tekens aan de wand. In de clumsy pamflettaire stijl die typisch is voor zowel het politiek activisme als het esthetisch anarchisme zijn ze ook een stille en bijna ontroerende vraag om aandacht van devianten die in hun leven heel veel (al dan niet geëngageerd) lawaai gemaakt hebben. Elk van deze acteurs die, hetzij als activist, hetzij als escapist, op het schouwtoneel vrijwillig ten onder gaat heeft behoefte aan aandacht. Het is van cruciaal belang dat de wereld zijn of haar verhaal kent. Als de wanhoopsdaad van Palach onopgemerkt voorbij was gegaan was zijn actie zinloos geweest. Als de literaire- en kunstwereld geen aandacht zou hebben gehad voor de acts die Burroughs, Bacon en Cobain ‘naast’ hun kunst opvoerden zou hun kunst zelf zinloos geweest zijn. En in hun uiterste focus op interveniëren in of ontsnappen aan de wereld is het dat wat ze gemeen hebben.

Tijd om onze aandacht te vestigen op het middenveld tussen de uitersten, want ik stel dat daar nog interessante figuren rondlopen die bovendien de twee uitersten binden. Het gaat over de politiek geëngageerde kunstenaar die in zijn acties op langere termijn denkt en niet zelfdestructief wil werken, en daarmee eerder opschuift naar de kant van de esthetiek, zoals de DDR kunstenaars waarvan sprake in de aanzet van deze tekst. Hun politiek activisme bestond ‘gewoon’ uit het maken van kunst waarvan de esthetiek door het regime strategisch niet getolereerd werd. Daarnaast staat in dat midden de solipsistische decadente estheticus die eerder zijn roes zoekt in gestileerd decor dan in het op de proef stellen van zijn of haar lichaam. De geëngageerde kunstenaar en de decadente estheet bevolken het middenveld tussen destructieve ethiek en destructieve esthetiek. Ze sturen geen postcards. Ze willen niet zelf in the picture staan, want wat ze gemeen hebben is dat ze gewoon niet geïnteresseerd zijn in het opvoeren van hun act in het publiek. Terwijl de sociaal geïsoleerde DDR kunstenaars voorbeelden waren van die geëngageerde ‘onbaatzuchtigen’ (l’art pour l’art, maar dan voor de goede sociale zaak) vormen de decadente solipsistische estheten een specialer ras. Om twee tekenende voorbeelden te geven in de context van dit verhaal: hadden ze er zin in gehad (maar dat hadden ze niet) zaten er tussen de postcards ook aankondigingen van ‘Joris-Karel in A Rebours‘ en ‘Brion in The Dream Machine‘. Joris-Karel Huysmans en Brion Gysin waren geen activisten of junkies, maar fijnzinnige estheten. In zijn roman A Rebours (Tegen De Keer / Against Nature) liet de romantisch-decadente schrijver Joris-Karel Huysmans zijn alter-ego Des Esseintes zich omringen met de duurste meubels en wandtapijten en zich vermaken met de fijnste parfums en likeuren. Des Esseintes leefde totaal teruggetrokken, liet zijn boeken inbinden in het kostbaarste leder, commandeerde exquise gerechten en fleurde zijn salons en boudoirs op met de zeldzaamste orchideeën. Zijn non-conformisme bestond uit het beleven van de persoonlijke uiterst doorgedreven esthetische ervaring zonder dat daarbij een openlijk misprijzen van de goegemeente moest opgevoerd worden. Maar Huysmans is ironisch, want hij laat het experiment van zijn geliefde estheet mislukken doordat die steeds op een vernederende manier geconfronteerd wordt met zijn praktische afhankelijkheid van mensen uit zijn omgeving (van kokkin tot tandarts). Brion Gysin vermeld ik speciaal omdat hij de intellectuele vriend van Burroughs was, doordachter maar daarom niet minder subversief. De kunstenaar en dichter Gysin was het dwepen met fysieke genotsmiddelen niet onbekend maar verkoos zijn esthetisch escapisme op een eerder conceptuele en licht ironische manier te beoefenen. Zijn ultieme zet was het ontwerpen van de Dream Machine. Een ronddraaiende rechtopstaande geperforeerde cilinder bevatte binnenin een simpele lamp, en het adagio was dat het met de ogen dicht beleven van deze stroboscopische flikkeringen een trip kon opwekken waarvoor men anders een lijn of twee nodig zou hebben. Zijn Dream Machine was dus een moderne ‘veilige’ roesopwekker die diegene op zoek naar bovenzintuiglijke ervaringen tegelijk ook een ironische spiegel voorhield. Maar ook Gysin was melancholisch in de wijze waarop hij als estheet steeds geconfronteerd werd met zijn eigen ‘beperkingen’. Niet alleen noemde hij zichzelf ‘born wrong time, wrong place, wrong colour’ (hij deed zijn coming out als homo in het Amerika van de jaren 40 en viel bovendien op zwarte mannen), op het einde van zijn leven noemde hij dat leven ‘a great adventure leading nowhere’ omdat hij naar eigen zeggen nooit had kunnen kiezen tussen schrijven of beeldende kunst. Vrienden noemden hem ‘a great something else’ maar wisten ook dat zijn cultstatus hem grote voldoening verschafte. Huysmans en Gysin zijn daarmee in eerste instantie ironische esthetische anarchisten in eigen kamp, en dat maakt hen verschillend van de uitersten hierboven beschreven.

In het spectrum gaande van politiek activisme tot sociaal escapisme staat de geëngageerde kunstenaar ergens midden tussen de activist en de junkie, en hij wordt geflankeerd door de decadente estheticus. Hun middenpositie is er echter geen van middelmatigheid, integendeel. De geëngageerde kunstenaar beseft dat, wil zijn actie enig effect hebben, hij zijn kunstenaarschap zou moeten opgeven, en de decadente estheticus beseft dat hij zich niet kan en wil loskoppelen van de wereld van de praktische beslommeringen. Palach, Parks, Burroughs en Bacon mogen elk op hun manier tragische figuren zijn, ze zijn niet melancholisch. De echte melancholische figuren zijn de geëngageerde kunstenaar met een politieke boodschap en de decadente solipsistische estheticus die zijn link met de natuur niet kan doorknippen. Ze sturen geen postcards, want niet alleen zijn ze niet geïnteresseerd in de vraag of de wereld van hun bestaan afweet, ze weten ook dat ze het publiek geen verhaal kunnen bieden dat tragisch is in zijn logica of logisch is in zijn tragiek, en dit omdat hun manifestaties steeds opnieuw onderuit gehaald worden door de werkelijkheid. Dit is geen pleidooi voor de melancholici ten koste van de tragici. We hebben ze allemaal nodig. Terwijl de politieke activisten en escapistische junks zich elk aan hun eigen kant vrijwillig slachtofferen en daarmee de grenzen van ons ethisch en esthetisch speelveld afbakenen en scherpstellen, herinneren de melancholici er ons aan dat non-conformisme van eender welke soort, hoezeer ook nodig, zich niet kan beroepen op logica. ‘ALTERNATOR – 23 Postcards From The Antipodes’ vertelt ons daarbij dat de ontmoetingsplaats van de melancholici en de politieke en esthetische tragici de jungle is; niet het natuurlijke oerwoud, maar de anti-establishment vrijplaats die op cruciale plaatsen bevolkt wordt door de vreemde vogels die Colin Waeghe op scène zet, en die open staat voor iedereen die durft. Die vrijplaats is geen locatie die in een reisgids kan aangeduid worden. Er gelden geen wetten van de sterkste en er heerst eigenlijk ook geen chaos. Als men er niet is wil men er naartoe, en eens daar wil men er terug weg. Daarom is het een onmogelijke én tegelijk mogelijke plaats. Voor die mens op zoek naar zingeving is die plaats dus haar eigen antipode, want ze vertelt hem dat zijn doel en lot niet meer en niet minder is dan het romantisch verlangen op zich.

Gaston Meskens, 13 maart 2011

show at Gallery Vandeweghe, Antwerp

See also www.theartsinstitute.org

Summary

Enlightenment and modernity provided us with the ideas, morals and practices of a rationalist science and a democratic politics, and thus also with the idea that a scientist or a politician can take up an enlightened and modern ‘mandate’ towards society. In our complex world of today however, in dealing with humanitary crisises, ecological threats and economic decadences, the credibility of the scientist and politician becomes more and more under pressure. Their defence, very often, results in strategic framings and populist simplifications of scientific and political argumentations, leading to polarisations that tend to serve a maintenance of the own comfort zone rather than a conciliation in the interest of reaching consensus.

This project reflects on what artistic social agency in the form of research or political activism can still mean today. It does however not have the ambition to ‘compare’ the agency of the scientist and the politician with that of the artist, and this for the simple reason that ‘credibility’ is not a relevant concept for the artist’s functioning in society: the contemporary artist is not elected, does not need to be objective and has nothing to prove. However, a (self)reflection on contemporary artistic research or activism practices may not only be interesting for the art world as such but essentially also for those scientists and politicians who find themselves confronted with the impossibility to reduce arguments on complex socio-political issues to simple ratios that would primarily serve their own legitimacies constructed around (their) truths and identities. In doing this self-reflection in the form of an art practice, art can thus keep up a ‘critical mirror’ in front of science and politics; a mirror that shows the ambivalence of their positions and unveils the problematic character of their eventual strategic misuse of this ambivalence…

Read full text + images here: A Topology of Agency – Feb 2012

Visit www.theartsinstitute.org for more on this project

perstekst:

Antwerpen, 24 september 2010

In Square 1 toont Narcisse Tordoir een reeks tekeningen, twee schilderijen, een video en een krant. De werken suggereren samen het bestaan van een oversized-sacraal schilderij dat niet te zien is. Het bestaat wel degelijk, maar wacht op een andere locatie in de stad om getoond te worden. Square 1 gaat, als in een spel, terug naar af. In een soort van time collapse duwen de werken de antropoloog, de socioloog en elke andere toeschouwer met hun neus op de feiten: of die feiten nu van vandaag of van 20000 jaar geleden dateren, wat er tussen mensen gebeurt kan alleen maar bekeken, interactief geïnterpreteerd en nooit ‘van op afstand’ ondubbelzinnig begrepen worden. En dit niet omdat we er ‘niet bij waren’, maar net omdat we erbij horen. De mens regisseert zijn rituelen en registreert ze in beelden. Die beelden zijn vandaag gepolijst, getrukeerd en gesofistikeerd, en neigen in hun populaire gemediatiseerde vorm weg te kijken van de geweldloze sacred horror die de mens ‘bovennatuurlijk’ nodig heeft. Square 1 toont dat er sinds het ontstaan van de mens wat betreft het ritueel van de liefde, sex en de dood niets veranderd is, maar ook dat het maken van kunst-beelden een essentieel onderdeel van dat ritueel is. De epiloog van de show is visuele leegte, bevrucht en besmet door wat vooraf ging, en dus klaar om opnieuw ingevuld te worden. (tekst : Gaston Meskens)

Text as it appeared in the publication of the show:

Wonderment is Cool (Cave Painting Today)

In “Square 1”, Narcisse Tordoir shows a series of drawings, photos and paintings, a video and a newspaper. Together, the works suggest the existence of an oversized sacral painting that is not on view in the gallery. It does exist, but it waits to be shown at another location in town. Although not displayed at the ‘principle’ public location, the work is not downgraded or dislocated. The official pragmatic reason for the fact that it is not shown there is that its dimensions surpass those of the gallery. The real motive for its erection at an off-peak location is different however: the painting is on view in the deepest, almost inaccessible part of the cave.

Stumbling into progress (a short story of humanity)

The development of consciousness and the talent of intelligent reflection made the human to live in a default a priori mode of wonderment. In this development, which is, as it is said, what distinguishes humans from other living creatures, wonderment manifests in three ways, being

1 / The awe for what is ‘outside’: the natural environment, its meaning and its origin;

2 / The puzzlement with respect to what is ‘inside’: the self, and its relation to the body and, based on the consciousness about the distinction between life and death, the subsequent fear for the death;

3 / The struggle to make ourselves understandable in interaction with the other, about this awe, this puzzlement and this fear, and about our relation to this other (with his awe, puzzlement and fear).

But despite of the oppressive character of these stances of wonderment, and despite of the growing consciousness of the complexity of it all, the early human being, who separated himself from the animals on the basis of his reflective capacities, had no time to sit back and reflect on the origin and meaning of nature and life or on more deliberate aesthetical or ethical modes of human interaction. Bare necessities needed to be met, and in the interest of this, man hunted, gathered and travelled, leaving one exhausted area for another promising place. Meanwhile, fear, awe and puzzlement were relieved through escape into unhierarchical collective rituals. With the change from nomadism to the living mode of settlement in self-sustaining agricultural communities, the practice of economic trade and the overall need for social functional organisation emerged. The structures of social organisation provided the incentives for the development of organised religion and science. These ways of making sense of the world apparently finally provided a cure for the human angst, as, in various parallel phases of civilisation, they both attempted to rationalise the stances of wonderment into big stories of belief or evidence of proof. Rituals became politicised and knowledge became a source of power.

And finally, out of the need for functional social organisation, the idea of social inclusion materialised easily, as it was only a matter of coupling the concept of social identity to a geographically demarcated living space. By keeping the group together, generation after generation, social identity gradually motivated social inclusion and vice-versa. But in this model of demarcated self-sustaining communities, the included became unavoidably occupied with conflict, intra muros with power struggles and extra muros with pillaging or defence against it (as it seemed easier to conquer another communities’ stock than to build up an own). The idea that safeguarding social identity is a bare human necessity was born, and all existing communities, identified by differentiation, agreed that this safeguarding should be done through protective inclusion and conflict and defensive exclusion and threat, and all of them shared the conviction that this approach, although regrettable, is an unavoidable aspect of the spirit of humanity.

And since then, nothing essentially changed.

That is: nothing changed about how humans think living modes should be organised and rationalised. Since the enlightenment, and especially during the last century, critical thinking and shocking war experiences challenged the beliefs in eternal spirits and empirical evidences, and technological progress brought global benefits and global problems. The bare plain in between the distinct gated communities has long been crossed and filled, and we all live now inside each others territories. The original idea of the community that, on the basis of the abstract notion of ‘inclusion by identity’, attempts to be self-sustaining through intercommunal trade and political protection is not longer relevant, and instead of realising that ‘inclusion by identity’ is a false approach that can easily be misused in oppressive power structures, we still try to solve our now globalised problems through this outmoded socio-political model. And still there seems to be no reason to critically but compassionately reflect on human wonderment, as still, fear, awe and puzzlement are relieved through collective rituals. They seem to be unhierarchical, as in their contemporary form, all humans have the freedom and right to buy the same products, spend their holidays in the same places and watch the same TV channels. The freedom and right is mediated and thus false, but most don’t care. They have no time to care, as bare necessities need to be met.

The unrecognised aesthetics of resignation

In September 1940, the paintings in the cave complex of Lascaux inFrancewere discovered. Although cave paintings were found in other places already, anthropologists were stupefied by the abundance of depicted scenes, the level of detail of the figures and the vivid colours used in this case. It became soon clear these works were about 17000 years old. They were created during theUpper Palaeolithicage and had been sealed of from the outside environment since then. The awe for the beauty of the complex was (and still is) accompanied with curiosity about the what and why of the depicted scenes, but also with a feeling of resignation, as we realise we have very little elements of knowledge to reconstruct and understand what the scenes represent. What is known is that, during that time, the Homo Sapiens coexisted with the Neanderthal man. Both are now considered as ‘human’ – in the sense of ‘different from animals’ – because they were both conscious of the difference between life and death. The burial rituals that can be reconstructed from archaeological findings show that these early human creatures, unlike animals, were terrified when faced with death. The rituals, including the offerings, were nonviolent and may be understood as a sign of respect for the deceased, but also as an attempt to protect the survivors against the mysterious power that took their tribe member away. The traveller-hunter-gatherer was a conscious but resigned and accepting human. He had no sense of the potential of settling in social organisation, but consequently also no sense of the threat of human conflict.

But a resigned consciousness affects the ways of expressing moods and impressions, and this has consequences. One essential thing distinguished the Homo Sapiens and the Neanderthal man: so far, our knowledge learns us that the Neanderthal man did not make art. Cave painting and sculpture are a typical thing of the Homo Sapiens, and in doing this, his genius separated him from the soon-to-be-extincted Neanderthal man. His genius is human in the sense of unnatural, as the art drawings may be seen as acts from out of pure wonderment, disinterested in the sense that they had no direct instrumental function in the daily struggle for survival. But immediately these drawings showed their magic power, as they provided a mean for these humans to express their fear, awe and puzzlement, either by making the drawings or by looking at them. One particular scene in the Lascaux cave suggests this in a unique but mysterious way. In the deepest, almost inaccessible part of the cave, a man with a bird-like head faces a bison in a hunting scene. While the man is drawn in clear but very rudimentary line, the animal is depicted with a high level of detail and colour use. Many interpretations have been made of this scene, but the one formulated by Georges Bataille in The Cradle of Humanity is interesting. He suggests both figures are dying, in front of each other, as in a mutual nonviolent sacrifice of complementary deaths: “…But this man at the heart of the cave’s recesses did not assume the proud and particularly personal heroism that is peculiar to modern times. He did not slip into this individual vanity that humanity perhaps found in war. … From the depths of this fascinating cave, the anonymous, effaced artists of Lascaux invite us to remember a time when human beings only wanted superiority over death.”

Long before science and organised religion aimed to present a rational case for wonderment, art provided a first innocent mean to make sense of it. The cave artist, as the magician, joined the technician (who provided weapons for the hunt) in being the first human intellectuals. Both had a different role, but, more important, both had no strategy. In expressing religious and erotic ‘moods’, the early human artists were innocent. Their innocence was genuine, but not deliberate. It could not be deliberate, as they were ‘first’, and they had no choice. But their unchosen intelligent-emancipating stance reminds us today that pure religion and eroticism, even in their most decadent forms, are unselfish and disinterested. As soon as humans imply them into a power structure, they become cruel. Cruelty, even in passive form, does not come with intelligent idleness, but with the stupidity of selfishness. The human being is not cruel by default, but innocent. But, in contradiction to cruelty, innocence brings along responsibility. And that is a hard burden to carry.

Civilisation, in the sense of streamlining human organisation into conformist patterns, self-rationalised on the basis of ‘natural’ tradition, organised religion and, recently, social sciences, is a therapy that focuses on the wrong disease. That is, it assumes human reflective wonderment is the disease that should be cured, instead of accepting it as that what makes us human. Wonderment is cool, and awe, puzzlement and fear are intelligent states of being, even so the melancholy that comes with the consciousness of all this. Human disinterested reflective wonderment is about curiously accepting limits to the knowable. But the modern human considers these limits as a temporary and intermediate phase in the linear process of human progress. Since the ‘enlightenment of the ratio’ and up till today, humanity did not accept yet that human natural, social, economical, scientific and political interactions are complicated by degrees of uncertainty, ambiguity and complexity that ‘by design’ cannot be cleared out. This denial, supported by as well postmodern relativists as (neo)conservative truth-seekers, has led to a general phobia for the unknown that gives way to all kinds of strategic rationalisations and simplifications in the social and political sphere. Today, ‘innovation’, in a thin understanding, aims to develop the technological human, but forgets to take along the philosophical human first. The reason is not that the latter would be too difficult to treat, but rather that it requires solidarity and, above all, engaged cultural relativism.

With our contemporary gaze blinded by the behold of today’s fictional and factional scenes of complacency, mediocrity and violence, and our mind and memory contaminated with the wearisome stories behind, are we still capable of grasping the essence of man’s first art works?

I claim the answer is no, but it doesn’t matter, as innocence can be reinvented. It can be reinvented in science and religion driven by disinterested curiosity and belief, and in art driven by disinterested empathy. But art is the only way of making sense that, at the same time, can be meaningfully conceptual-ironic, conceptual-decadent and conceptual-aesthetic. It makes sense because it takes wonderment serious while acknowledging it cannot provide answers. The short story of humanity, as told in the first part, was obviously incomplete, as art was not mentioned.Lascauxreminded us that art is the ultimate medium to make sense of wonderment, as it is the only way of making sense that provides a cure for wonderment without treating it as a disease.

Narcisse Tordoir’s compassionate research in the visual arts

From today’s perspective, the contemporary art world would call theLascauxpaintings outsider art. Outsider art is that kind of visual art that, according to the included, ‘misses the point’. That point is the point of no return: since the emergence of modern art, and especially of conceptual art, visual art always ‘conceptually’ shows/suggest/tells more (or less) than what is visually detectable. As a deliberate act, this performance can be regarded as a new achievement in the human intellectual programme of ‘compassionate but unstrategic making sense of wonderment’. It may be that we do not understand yet what conceptual art is.

It is senseless to judge whether the early Homo Sapiens missed the point or not. His work may have been conceptual too, and we will never know. This is one message of Square 1. The show goes back, back to where we belong. In a time collapse, the works face the facts: whether these facts date of today or of 17000 years ago, what happens in between people can only be observed and interactively interpreted, but never objectively understood ‘from a distance’. The reason is not that we were not part of the game that time, but simply because we are always part of the game. The human being directs his rituals and captures them in images. Today those images are polished, tricked and sophisticated and in their popular-mediated form they tend to look away from the nonviolent supernatural sacred horror the human being is craving for.

Square 1 is conceptual in its innocence. The work is innocent, but obviously not naïve. It is not naïve because the deliberate intelligence emerges from the process the physical works have undergone. They are the remainings of a double re-enactment. The first is a replay of theLascauxscene mentioned above. The rudimentary man is now split into a diverse group of actors, while the diverse group of animals is collapsed into one rudimentary animal-like sculpture. The actors adopt a pose of disinterest. In their helplessness and mannerist unstrategic poses, they are supported by an animal that seems to be nothing more than a wooden frame and a pathetic Disney-style face. The animal can’t help, and neither can the actors, because, compared to the figures in theLascauxcave, they are now conscious of what happened to nature and humanity meanwhile. The mask of the suicide terrorist is actually the mask of a sadomasochist, not of a self-proclaimed or mislead hero. The re-enactment of the happening is only half of the work. Narciss Tordoir also ‘re-paints’ the painting of the scene. The paintings and drawings on view suggest they have already been painted once before. For Narcisse Tordoir, painting is an instrument to create an image of painting.

Square 1 is a compassionate-ironic ode to the nonviolent, to the nonviolent supremacy of human wonderment in its manifestations of fear for the death, puzzlement about the self and awe for nature and the other. The works show that since early humanity nothing has changed in the ritual of love, sex and death, but also that the creation of art-images is an essential part of those rituals. The epilogue of the show is visual emptiness, fertilised and contaminated by what preceded, and thus ready to be re-enacted, again.

Epilogue – the critical aesthetics of reticence

[letter to Masashi Echigo following my visit to his studio at the HISK, Ghent]

Antwerp, 13 July 2010

Hello Masashi

The first thing that came to mind after leaving your studio was that you need a biographer as soon as possible. From what you told me, I understand that virtually nothing of your work remains, and that you do not consider the photos of your temporary installations as being art. You also have no website or blog, and to my knowledge no intention to make one. On top of that, due to the fact that you move from one place to the next, there is no possibility for your environment (that is: for the people you interact with) to construct some kind of collective memory. The memory of your interventions is fragmented and ‘in the hands’ of many different people, places, and institutions.

Now you could of course ask: why would it be necessary to trace, collect and archive what I did in the past? If people find what I do important, they will trace, collect and archive what they themselves have encountered, and if somebody wants an overview, s/he can simply search for it on the internet.

I think I have an answer to this. You told me that you used to live in a too-small living space in Japan, and that this fact might be one of the reasons you are a wanderer. I think there is more at stake here. The fact that you make installations with borrowed objects and that you return these objects afterwards is to me crucial in your work. It is almost as if you want to make sure that nobody can discover the work afterwards. By removing any trace of the physical work and, more importantly, by giving the material back to the owners and thus once again rendering the borrowed ‘found objects’ to the non-artistic status of their everyday physical appearance and use, you actually split your audience into two groups. The general public who saw the show will remember it, as per any other conventional display. But you have an extra and special category of audience that is meaningful to you in what you do: the people who fabricated materials and lent you objects for your work. They will not only remember the work, but also you. Whether you want them to or not, those people will first memorise their encounter with you, your passage, and then the work. Therefore, your encounters are to me part of your work, every bit as much as your arrivals in each place and departures to the next…

That is why I think the whole of your story should be documented in some way. I know that both extremes (either making a plain chronological overview yourself or leaving it up to others and the internet to represent you) are not real options. It should be something in-between, a hybrid virtual presence, eventually maintained by a network of the people you have interacted with…

[statements on…]

Effacing manifestations

Today, in a world where any artist can declare any object or act to be a work of art, and where the cult of ‘the artist as a public person’ tends to overshadow the very existence and expressive function of the artwork itself, the focus on questions related to artistic sincerity and credibility has evidently and definitely shifted from the art itself to the artist ‘behind’ the work. Many contemporary artists would deny this, and stress that artistic freedom should not be jeopardised by critical scrutiny of intentions and validity claims. They would miss the point, as what is at stake here has nothing to do with freedom. The public artist is as liberal as the one who chooses to remain invisible, but the first must accept that the public performance is unavoidably part of the artwork as such. And this has consequences.

Artists have always profiled themselves ‘alongside their work’ but, certainly today, creators tend to figure at the centre of attention more-so than their creations. Art magazines display artists on the cover instead of artworks, and, almost by default, artists give interviews and comment on their new work, as well as on anything else that happens in society. While there would be nothing problematic with this phenomenon in principle, one can observe that the artists that are most prominently in-the-picture tend to be those who keep on repeating that their work ‘speaks for itself’. Those artists cannot be remembered, as they are always there, prominent in the picture, standing in front of their work instead of aside or behind it. Their work is absolute, rewarded with a self-declared iconic masterpiece status and thus meant to stay. At the same time, however, they block the view of that work, with the aim of promoting and explaining it, in order to make sure that it cannot be overlooked or misunderstood.

The very least one can say is that the behaviour of Masashi Echigo is completely opposite to that sketched above. Although figuring as a mediator of self-selected processes, he adapts his work to the context, the décor and the scenery of each venue that has been proposed to him as a possible next stop. When finished, he mostly remains out of the picture (let alone positions himself in front of the work), is reluctant to take the initiative to talk about it, and, if the work is not ‘saved’ by a gallery or museum, makes it disappear again after his passage.

While this creation process may seem to have a somewhat problematic, ad hoc character in the way it appears to be driven only by external incentives and spurs, nothing is less true. Masashi Echigo is an artist with a plan and, one may even suspect, a strategy. But his plan is that of the passenger, of the silent intelligent interventionist, and his strategic aim behind it is not self-serving publicity but interactive self-reflection. The physical work is not made with the intention to have it transcend and survive the contexts, décors and sceneries from whence it emerges. The few objects that remain in existence as autonomous art works are those that were saved by the people around him, and thus serve as the exceptions that prove the rule. What is meant to survive is the story of the encounter, including a memory of how things were before, and an indication of how things might have changed when, following that encounter, actors, objects and pieces of décor resumed their original affairs.

Protective isolations

The objects Masashi Echigo uses in his works, such as Belongings, Grensland, Under Tension and Epistrophe are ‘found’, but they are actually the opposite of readymades. Since its original conception by Marcel Duchamp, a readymade was meant to retain a declared artistic status, although it could exist in multiple versions authorised by the artist. I maintain that introducing the readymade was, however, not an act of arrogance, but a call for modesty (and therefore probably even more provocative). And therein is a likeness with Masachi Echigo’s found objects. In their origin, they are also appliances or decorative pieces that fulfil a functional non-artistic role in daily life, whether as part of the private belongings or homely décor of local citizens, or of the perfunctory scenery of an institution. And in regard to Masashi Echigo’s artistic interventions, these objects are also lifted out of their banal function and rewarded with an artistic status. Symbolically, however, they do not become autonomous art objects themselves, but instead are privileged to figure in a specific solemn enactment. In contradiction to readymades, they don’t lose their history or functionality in this figuration, but remain filled with their everyday trivial but essential private narrative, which also implies that they cannot be created and authorised in multiple versions. The whole act is a ceremony in honour of these fragile narratives. In addition, the objects are often encaged, not to prevent them ‘standing strongly in public’ (as a readymade would do), but to protect them from critical outside interrogations on the relevance of their private character in reaching higher artistic ends.

[epilogue…]

Only months after I raised my concern about the need to start to document the work of Masashi Echigo, a first realisation materialised, further to this suggestion, in the form of this book. This occurence is to me a nice surprise as well as a logical evolution. Moreover, the book can indeed be seen as that ‘hybrid virtual presence, maintained by the network of people who have interacted with Masashi Echigo’.

Having declared Masashi Echigo’s encounters, artworks in themselves, the ‘stories’ are testimonies of these works. They need to be traced and preserved in the first instance as per those self-satisfied artists mentioned above, with the aim of balancing their omnipresence with his deliberate absence. But the final message is positive. His plan is not to ‘hold a mirror’ to society or the art world. Instead he places a window of reticence in-between his audience and his physical installations. The window is an intelligent filter that reminds us that today, whether meant poetically or politically, art is what we make of it, by way of mutual agreement. Thereby, any declaration of absolutism can be better ‘only’ if meant poetically, as the alternative would be naïve or dangerous, or both. Masashi Echigo’s work is critical in its enduring silence, and poetical in its hesitant temporal gravity. There are many more stories to come.

xxx